When a billion users meet privacy choices, traditional design breaks

OpenAI's decision to kill their chat discovery feature after users accidentally shared private conversations reveals why AI privacy design needs new approaches—not just better warnings.

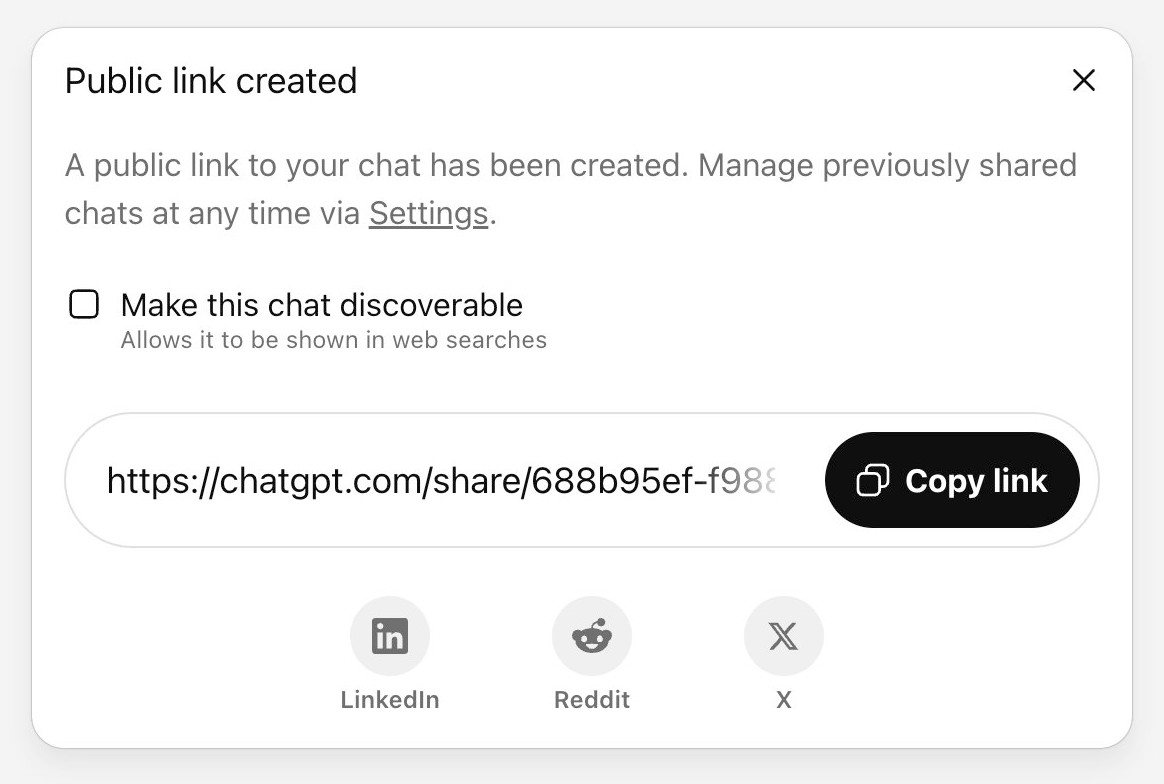

Traditional privacy design assumes users will read, understand, and make informed choices about their data. OpenAI just learned what happens when that assumption meets a billion-user AI platform. Their "discoverable chat" feature seemed straightforward—a checkbox to "make this chat discoverable" with Google and other search engines. Users ended up inadvertently exposing intimate conversations to public search results. OpenAI pulled the feature.

Simon Willison's analysis of the interface reveals the real challenge. Even clear language like "allows it to be shown in web searches" requires users to understand URLs, search engine mechanics, and the permanence of online content. We're asking every ChatGPT user to think like a privacy professional before clicking a box. When Dane Stuckey announced the feature removal, citing "too many opportunities for folks to accidentally share things they didn't intend to," he was acknowledging that informed consent through disclosure doesn't work for billion-user platforms.

Meta AI shows the same problem with their "Post to feed" button, despite what Willison calls "top notch" microcopy. Clear language helps, but it can't bridge the gap between what interfaces ask and how people actually behave. When people focus on completing a task, they often click through privacy options without reading them, regardless of how well-written they are.

What's needed isn't better privacy notices or more prominent warnings. AI privacy design needs to flip the traditional model—making privacy protection the default and creating intentional friction for any action that compromises privacy. This means rethinking how we get consent, building systems that protect users from their own attention patterns, and accepting that choice architecture matters more than choice disclosure.

For legal teams developing AI products, this means rethinking how we approach compliance. We're moving from compliance through user choice to compliance through protective design. The conversation about AI privacy isn't heading toward better disclosures—it's heading toward systems that work even when users don't read them.