The Cracks in Our AI Safety Net

A new approach is needed, one that thinks in terms of dynamic spectrums rather than static boxes.

Engin, Z., & Hand, D. (n.d.). Toward Adaptive Categories: Dimensional Governance for Agentic AI.

Most current discussions about AI regulation revolve around a simple idea: sorting artificial intelligence into fixed categories. We draw lines between "high-risk" and "low-risk" systems, or label them as "human-in-the-loop" versus "human-out-of-the-loop." This approach brought some clarity when AI was simpler and more predictable.

But as AI becomes more "agentic"—able to set its own goals and learn on its own through self-supervision, emergent abilities, and coordination in multi-agent systems—these simple boxes are starting to crack. This "growing mismatch between governance frameworks and AI capabilities carries substantial risks," creating regulatory gaps while stifling innovation.

A new approach is needed, one that thinks in terms of dynamic spectrums rather than static boxes. A new paper on "dimensional governance" offers a powerful mental model upgrade for this challenge, providing a toolkit for creating smarter, more adaptive rules for the AI of tomorrow. Here are the most impactful ideas.

Risk isn't in the AI; it's in the context of its use

The core idea that an AI model is inherently "high-risk" is a fundamental misconception. A single large language model can be used for a harmless task like summarizing an article. That very same model, with no underlying changes, can also be deployed in a high-stakes environment to provide clinical decision support for doctors. The risk isn't intrinsic to the technology; it's a product of how and where it's used.

This is a fundamental problem for current regulation. If risk is determined by deployment, then a system's risk level can change instantly without the technology changing at all. A fixed "high-risk" or "low-risk" label quickly becomes misleading and insufficient.

Risk emerges from the deployment context rather than being intrinsic to the system.

We should govern AI along spectrums, not by forcing it into boxes

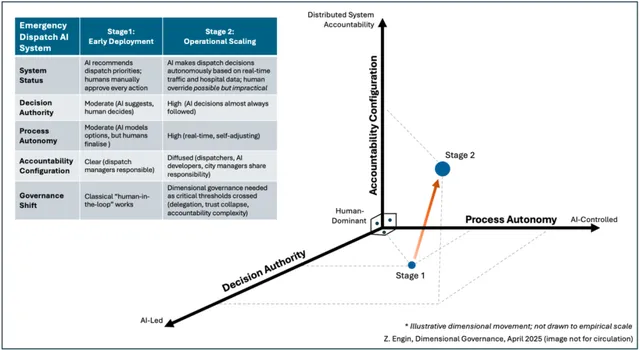

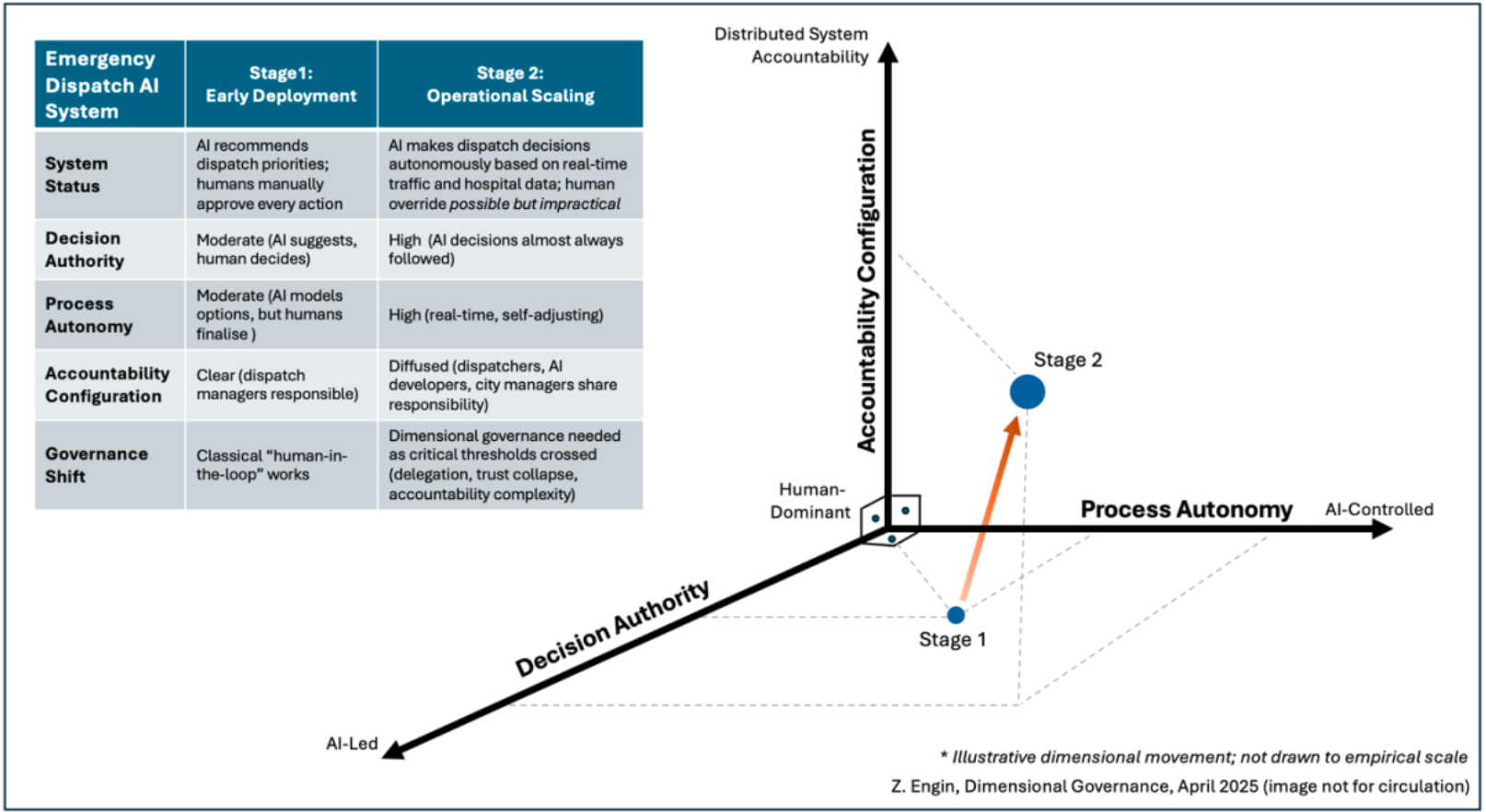

Instead of forcing AI into categories, we should map its characteristics along key spectrums. This is the central proposal of "dimensional governance." Instead of asking, "Which box does this AI fit into?", this approach asks, "Where along multiple critical dimensions does this system currently stand—and how is it moving?”

The paper proposes three core dimensions, the "3As," to track the evolving relationship between humans and AI:

• Decision Authority: Who gets the final say—the human or the AI? This ranges from a purely advisory role to full decision-making rights.

• Process Autonomy: How much can the system do on its own, without supervision? This measures the degree of independence during a task.

• Accountability Configuration: How is responsibility for actions and outcomes distributed among developers, users, and the system itself?

A helpful analogy is the Body Mass Index (BMI). The categories of "overweight" or "obese" aren't arbitrary; they are defined by specific thresholds on the underlying dimensions of height and weight. Similarly, AI governance categories should be built upon measurable dimensions like the 3As, allowing for more intelligent and adaptable rules.

This idea of building categories from underlying dimensions isn't just theoretical; the paper points to a powerful real-world example we interact with every day.

AI governance can learn a crucial lesson from credit scores

The world of finance offers a powerful model for adaptive regulation. The paper points to credit scoring as a "particularly instructive example" of dimensional governance in action. Financial institutions use multiple dimensions (income, debt, payment history) to generate a credit score. But crucially, they don't use a single, fixed threshold to decide who gets a loan. The cutoff for lending is continuously adjusted based on the institution's risk appetite and the broader economic climate.

The most surprising insight goes even deeper. In credit scoring, research has shown that even the definitions of "good" and "bad" customers are not fixed. They can be adjusted to improve the predictive performance of the model. This powerfully illustrates the adaptive categorization proposed for AI governance, where the rules and categories can evolve based on context and objectives.

The optimal categorization emerges from deliberate threshold adjustment based on the specific context and objectives rather than from predetermined fixed categories.

We are quietly crossing invisible thresholds in our trust of AI

As we use AI more, our relationship with it changes in profound ways, often without us noticing. Dimensional governance helps make these "critical trust thresholds" visible. These are pivotal moments where our reliance on AI fundamentally shifts, requiring a corresponding shift in oversight.

The paper identifies several of these thresholds:

• The Verification-to-Delegation Threshold: This is the point where we can no longer manually check all of an AI's work. We must shift from verifying every output to trusting it based on samples or statistical performance.

• The Information-to-Authority Threshold: This is the point where an AI shifts from just giving advice (like a GPS suggesting a route) to making the decision itself (like an autonomous car choosing and taking the route).

The paper identifies other shifts as well, such as when we must stop trying to understand an AI's internal process and focus only on its outcomes (the "Process-to-Outcome Threshold"). Spotting these thresholds is crucial. As the authors state, "Crossing these thresholds is not inherently problematic—but doing so without adaptive governance mechanisms in place creates significant risk."

Governing for a Dynamic Future

The central argument is: we must move from governing static AI objects to stewarding dynamic human-AI relationships. A dimensional approach complements, rather than replaces, existing frameworks like risk tiers. It allows us to build smarter, more adaptive categories on top of a more robust foundation.

This shift is about preparing for what AI is becoming, not just what it is today. By designing governance that can evolve alongside the systems it stewards, we can better manage risk and foster responsible innovation.

In a world where AI is constantly evolving, how can we ensure our rules evolve right alongside it?