PSR Field Report- What actually works: final observations from two days at PSR 2025

After two days watching practitioners solve problems that didn't exist two years ago, a pattern emerged. The sessions that landed weren't about perfect frameworks. They were about what works when building under constraints.

In October, I spent two days at IAPP Privacy. Security. Risk. 2025 in San Diego, watching 500+ practitioners try to solve problems that didn't exist two years ago. The conversations kept circling back to a tension I've written about before: we're building AI systems faster than we're building accountability structures around them. What struck me wasn't the regulatory uncertainty—that's nothing new. It was how the gaps between what developers build, what deployers control, and what regulators expect are creating real operational problems right now. Over the past few weeks, I've been sharing field notes on where the handoffs are breaking down and what that means for teams trying to ship responsibly. This final post brings it back to the foundation: you don't need perfect frameworks or massive teams to do meaningful privacy work. You need the right focus and the willingness to start.

What actually works: observations from two days at PSR 2025

After two days at IAPP's Privacy. Security. Risk conference in San Diego, watching 500+ practitioners wrestle with problems that didn't exist two years ago, a pattern emerged. The sessions that landed weren't about perfect frameworks or waiting for regulatory clarity. They were about what works when you're building under constraints.

Here's what mattered for product, privacy, and legal teams trying to ship responsibly.

Define boundaries, not every possible action

The AI agent governance conversation revealed something practical: trying to get consent for every action creates consent fatigue. The better approach is scope limitation. Define what agents cannot do rather than trying to predict everything they might do.

This maps to how we think about permission structures. Instead of asking "what should we allow," start with "what must we prevent." The boundary defines the safe space. Everything inside that boundary can move faster.

Build infrastructure that makes rights exercisable

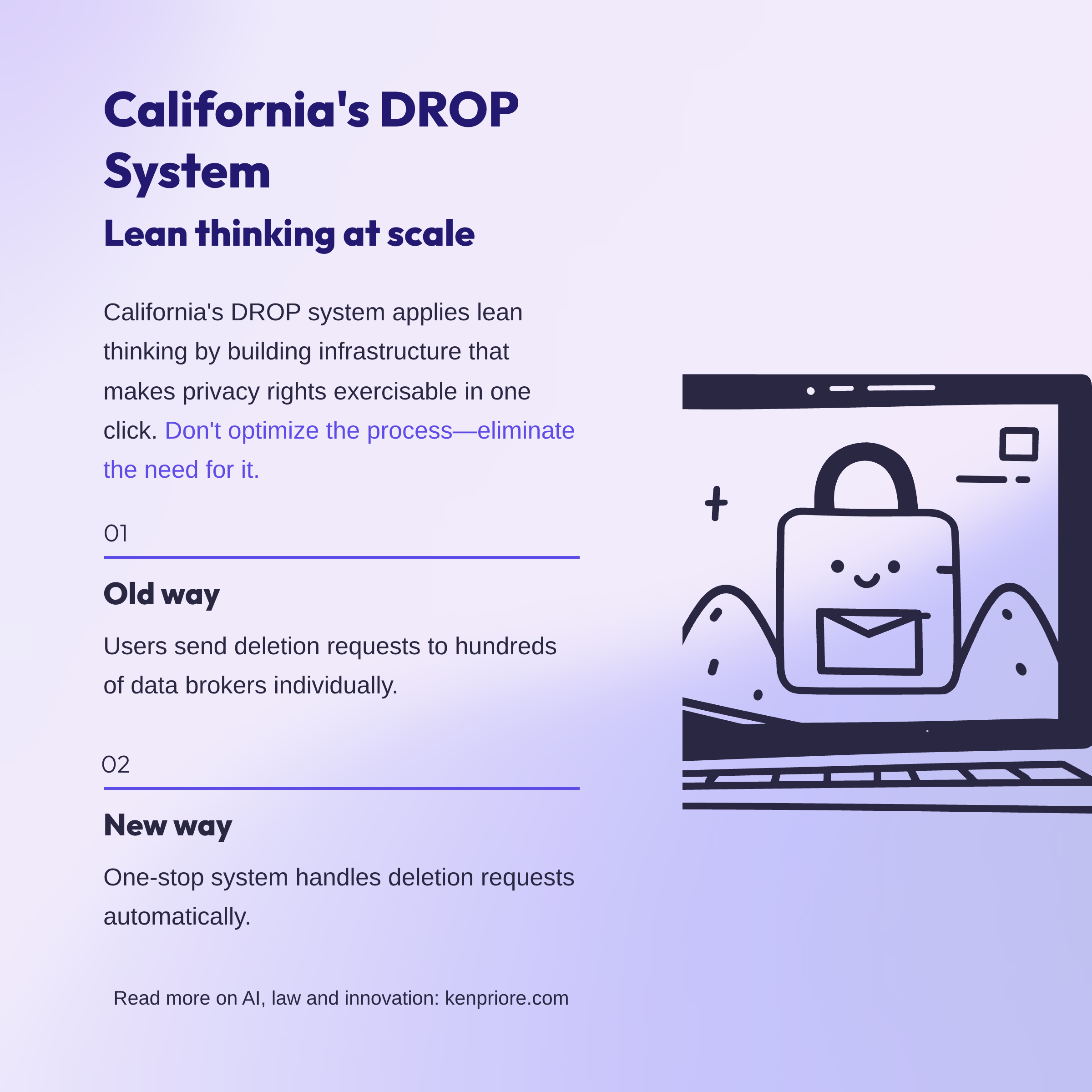

California's DROP system shows a different way to think about privacy rights. Instead of refining the process for users to send deletion requests to hundreds of data brokers, they built infrastructure that eliminates the need to do it individually.

One-stop deletion. Mandatory opt-out signals in browsers. This is infrastructure thinking applied to privacy. Don't make users work harder to exercise their rights—make the system do the work by default.

For product and legal teams, this means asking: are we making compliance the user's job or the system's job? The organizations getting this right are encoding requirements into architecture rather than relying on individual user action.

Match decision rights to where expertise sits

The upstream-downstream divide highlighted something that matters operationally: neither developers nor deployers can fully manage AI safety alone. Clear handoffs matter more than trying to create total oversight at every layer.

This means defining decision rights that match where expertise actually lives. Developers building with safety constraints. Deployers configuring for context. Governance monitoring and adapting. When handoffs are clear, each layer can do what it does best without waiting for approval from layers that don't have the right context.

Build governance that reduces uncertainty

Jessica Hayes' framework worked because it focused on political reality inside organizations. Walking in P&L owners' shoes. Understanding engineering constraints. Building controls that product teams want to use because they reduce uncertainty rather than just adding process.

This is the difference between governance that helps teams move and governance that creates bottlenecks. When legal and privacy teams understand business constraints and technical limitations, they can build controls that add value instead of just adding friction.

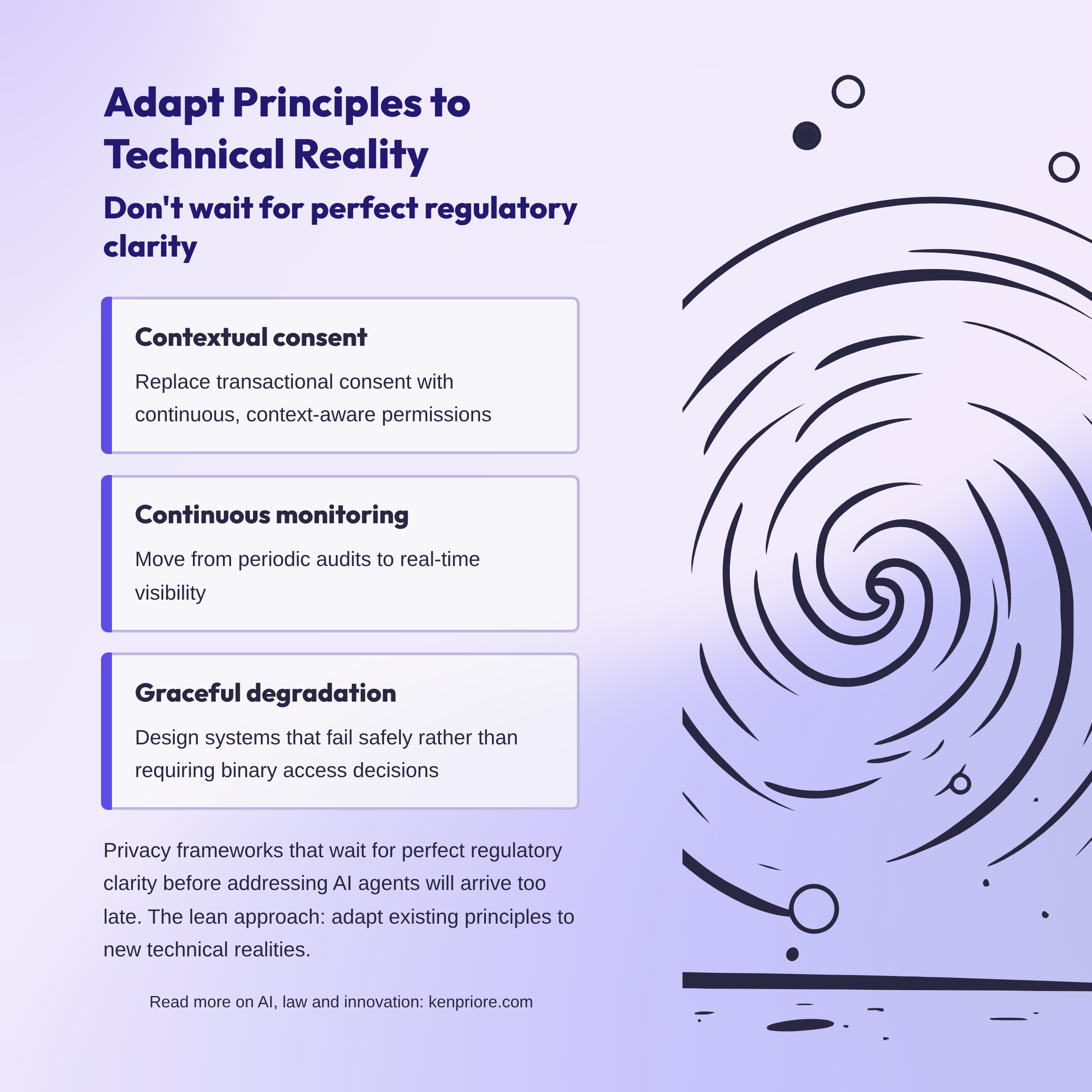

Adapt principles without waiting for perfect clarity

Privacy frameworks that wait for complete regulatory clarity before addressing AI agents will arrive too late. The practical approach: adapt existing principles to new technical realities.

Contextual consent over transactional consent. Continuous monitoring over periodic audits. Graceful degradation over binary access decisions. These aren't new principles—they're established approaches applied to new contexts.

For legal and product teams, this means working with the principles we have rather than waiting for regulators to write perfect rules for AI. The foundation exists. The question is how we apply it to systems that work differently than what came before.

Coordinate through systems, not committees

Breaking down silos isn't about creating cross-functional governance committees that meet monthly to review AI deployment decisions. That's bureaucracy pretending to be coordination.

Real coordination comes from shared accountability structures, decision rights aligned with expertise, and technical systems that encode governance requirements so coordination happens by default rather than by meeting invitation.

When governance is built into architecture, teams coordinate through the system itself. Privacy requirements become deployment constraints. Security controls become architectural defaults. The system does the coordinating.

Start focused, not perfect

The throughline connecting everything: start with the highest-impact problems. Build the minimum viable governance that addresses them. Ship it. Learn from what breaks. Iterate.

California isn't waiting for the perfect privacy law—they're building tools that make existing rights actually usable. The organizations getting governance right didn't build elaborate frameworks before starting. They built approaches that healthcare staffing professionals or legal teams or product managers can actually use.

Define purpose clearly. Make data flows visible. Detect violations in real time. That's enough to start.

Make hard choices about focus

Not every AI use case needs the same level of scrutiny. Not every data flow requires the same controls. Not every decision needs full documentation.

Figure out where the real risks are and put your resources there. Accept good enough for everything else. This isn't about lowering standards—it's about recognizing that treating everything as equally risky means you can't focus properly on what actually matters.

Build governance that scales with your team

If you have one privacy professional reviewing every AI model deployment individually, that doesn't last. Build architectural controls that make safe deployment the default. Create decision frameworks that let product teams move without waiting for legal approval on every choice.

This scales. Individual review doesn't.

Measure outcomes, not activity

Counting privacy reviews completed or policies updated tells you about activity. Understanding whether agents are staying within defined scope, whether data access aligns with purpose, whether users can actually exercise their rights—that tells you about results.

The difference matters. Activity metrics feel productive but don't tell you if the governance is working. Outcome metrics tell you what's actually happening in production.

Accept that privacy work is never finished

You're not building toward a state of complete compliance that you maintain indefinitely. You're continuously adapting to new technologies, new regulations, new business models, and new risks.

The organizations that succeed with AI privacy won't be the ones that build perfect frameworks before they start. They'll be the ones that start with focused, practical approaches and adapt as they learn. They'll build governance that helps teams move. They'll create tools that work rather than policies that don't. They'll coordinate across functions without creating bureaucracy.

Start where you are. Use what you have. Do what you can. Then iterate based on what you learn.

When AI capabilities evolve faster than policy cycles, shipping imperfect solutions beats perfecting solutions that never launch. The conference asked: How do we build trust when technology moves faster than frameworks?

The answer: one practical solution at a time, learning as we go, focusing relentlessly on what actually reduces risk.

That's not just a privacy approach. It's the only approach that works when the pace of change makes perfection impossible and delay unacceptable.