In October, I spent two days at IAPP Privacy Security & Risk 2025 in San Diego, watching 500+ practitioners try to solve problems that didn't exist two years ago. The conversations kept circling back to a tension I've written about before: we're building AI systems faster than we're building accountability structures around them. What struck me wasn't the regulatory uncertainty—that's nothing new. It was how the gaps between what developers build, what deployers control, and what regulators expect are creating real operational problems right now. Over the next few weeks, I'll be publishing a series of posts pulling out the patterns I saw. These aren't conference recaps. They're field notes on where the handoffs are breaking down.

So there was this interesting theme in many of the presentations at IAPP. Model developers and deployers operate in different parts of the AI development process, making different decisions with different visibility into risk. Neither can manage AI safety alone, but the transfer of responsibility between them is quite fuzzy.

Model developers work upstream—training, evaluation, deployment decisions that shape what's possible. Safety work happens in parallel with building: red teaming, adversarial testing, model cards documenting limitations. The constraint: developers can't anticipate every downstream use case. A model trained for general reasoning gets deployed in contexts the developer never imagined.

Deployers work downstream. They're making decisions about what agents should do in their specific contexts, setting access controls, defining procedures for handling problems. But they face a different constraint: they often lack visibility into how the model works. Traditional vendor due diligence doesn't translate. You can't just audit the code. The risk profiles are dynamic, not static. And users are making authorization decisions at the interface with even less visibility than either party—clicking through permissions without understanding what they're actually enabling or what system architecture sits behind it.

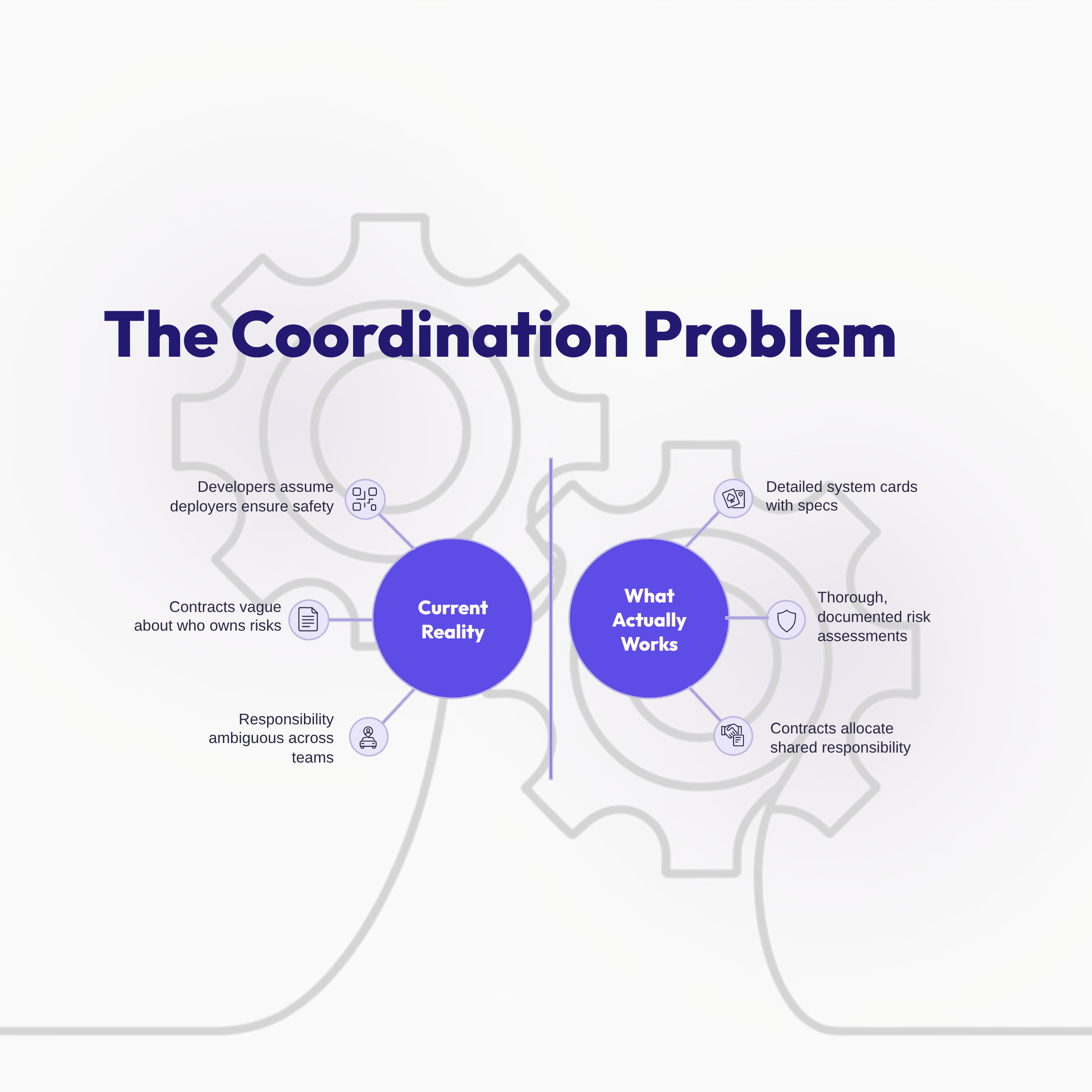

This creates a gap in oversight where everyone assumes someone else is handling it. Developers think deployers will add necessary protections. Deployers think developers have already built in sufficient safety measures. Users assume that being asked for permission means someone upstream has already determined these are reasonable requests. Everyone is partially right and entirely wrong.

The contractual problem compounds this. Current vendor agreements don't clearly allocate responsibility for AI system performance and impacts. Who's liable when an agent makes a decision that goes wrong? The model provider? The company that deployed it? The answer is usually "it depends"—which won't work when you're trying to build clear accountability. And users? They're not party to these contracts, but they're the ones dealing with the consequences when accountability falls through the cracks.

Julie Brill's observation about her time at Microsoft was striking: the role required more political skills than her work in DC policy. AI governance inside large organizations means legal teams aren't just interpreting regulations—they're negotiating with business unit leaders, engineering leads, and product managers, all operating under different incentives and timelines. The user perspective rarely has a seat at that table—the people actually interacting with these systems aren't consulted about the trade-offs being negotiated in their name.

The Trump administration's AI action plan added another layer. While positioning itself as "pro-innovation," the regulatory activity tells a different story: export controls on semiconductors, government stakes in chip companies, and ideological requirements for procurement. The "deregulation" narrative doesn't match the day-to-day work of navigating multiple, sometimes conflicting, regulatory interventions.

What works? Developers publish detailed system cards that give deployers information they can use. Deployers conduct thorough risk assessments before deployment and monitor after. Giving users actual control over agent actions, not just permission prompts designed to be clicked through. Designing interfaces that surface risk in context rather than burying it in terms of service. Contracts that clearly define shared responsibilities rather than trying to push all liability one direction. And ongoing dialogue between upstream and downstream teams about where risks are showing up in practice.

The upstream-downstream divide isn't going away. But it becomes manageable when both sides recognize they're working on different parts of the same problem—and that neither can succeed without clear transitions and shared language. And users sit at the endpoint of all these handoffs, expected to make informed decisions about systems whose architecture, limitations, and risk profiles remain fundamentally opaque to them.