Decision models: Making AI decisions auditable before deployment

Show me the decision logic. Not a vague explanation. An actual specification.

A loan application gets denied. The customer asks why. Your AI system returns: "Based on multiple factors, your application doesn't meet our criteria." Legal counsel asks the same question. The system gives the same non-answer. That's a problem.

Legal teams reviewing AI systems for loan approvals or risk assessments should ask one question: show me the decision logic. Not a vague explanation about model training. Not a promise that the LLM "usually gets it right." An actual specification showing how inputs map to outputs, what rules govern edge cases, and where the authority for each rule comes from.

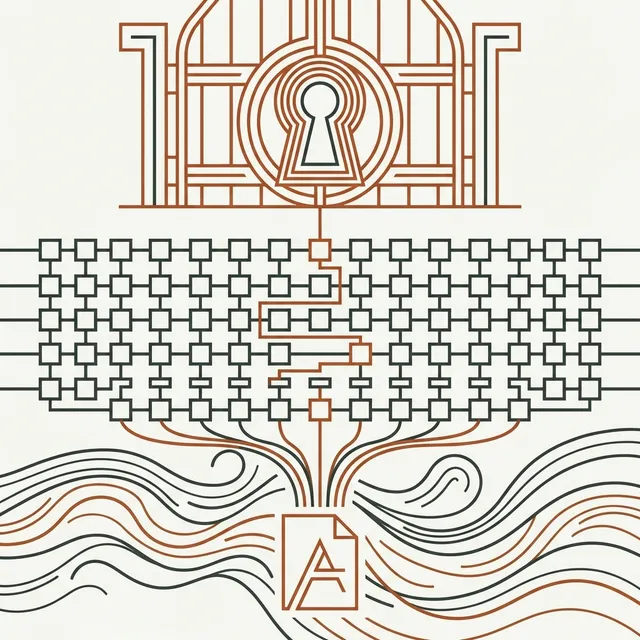

There's a solution. It's called Decision Model and Notation—decision models that replace probabilistic reasoning with deterministic rules where consistency matters more than flexibility. Based on "A Beginner's Guide to Decision Model and Notation (DMN) for AI Agents," this framework gives product teams a way to build decision components that pass legal review because the logic is visible, the dependencies are mapped, and the authority trail is documented before deployment.

What decision models do and why they exist

Decision models are a standard for mapping business decisions. Instead of hiding logic inside opaque processes, they represent each decision as a visible, connected component. A loan origination system has a main decision—approve or deny this application—that depends on subdecisions about credit tier, loan-to-value ratio, and vehicle type. Each subdecision has its own logic specification and links to the policy document or regulation that governs it.

Decision models exist because language models produce inconsistent outputs for the same inputs and provide no mechanism for tracing a specific answer back to a specific rule. Decision models solve both problems by making decision logic explicit rather than emergent. You define the conditions, specify the outputs, link each rule to its source document, and get a system that produces the same answer every time for the same facts.

For legal teams, that consistency means you audit the logic before deployment rather than discovering errors through post-hoc review of production outputs. For product teams, it means you iterate on decision rules without retraining a model or hoping prompt engineering will force the right behavior.

How decision decomposition creates reusable components

Decision models work by breaking decisions into smaller pieces. Start with the primary question—should we approve this loan, and on what terms?—then break it down into smaller questions that must be answered first. What type of vehicle is being financed? What's the applicant's creditworthiness? What's the loan-to-value ratio? Each subdecision becomes its own defined component with explicit logic.

These components work across different parent decisions. The credit tier logic you define once feeds into loan origination, marketing promotions, and account review processes without rewriting the rules. When you update how credit tiers work, every decision that depends on that component inherits the change automatically. Decision models work as "views into a network" rather than standalone procedures, which keeps your decision architecture organized as systems get more complex.

The decomposition also clarifies what information each decision needs. The loan origination decision requires raw vehicle data as input—make, model, condition, value—plus the outputs from the three subdecisions. That distinction matters because input data comes from external systems or user submissions, while subdecision outputs come from other decision model components. Legal teams reviewing the model can trace exactly which facts drive which conclusions and verify that each dependency has a documented source.

Decision tables contain the actual logic

Decision tables specify the rules. Left side: conditions (vehicle condition, vehicle type, LTV rating, credit score). Right side: outcomes. Each row is one rule. When all conditions in a row match, that rule fires.

If vehicle condition is "new" AND vehicle type is "boat" AND LTV rating is "good" AND credit score is "excellent," the outcome is "approve."

Rows work like OR conditions across the full table. The system evaluates each row in sequence until it finds a match, which means you can cover multiple paths to the same outcome. Two different credit score combinations might both lead to approval if other factors compensate. The table format makes completeness checking straightforward—legal counsel can scan for gaps where no rule covers a valid input combination.

Decision tables are the most common logic format, but decision models also support if-then-else statements and mathematical functions when rules don't map cleanly to tabular structures. The key requirement is deterministic logic. Given the same inputs, the system must produce the same output every time. Transformers don't work this way.

Where machine learning models fit

Decision models don't eliminate ML. They draw a clear line between probabilistic predictions and deterministic business rules. A default risk model might produce a probability score based on historical loan performance data, but the final approval decision uses that score as one input among several in a decision table. The table defines thresholds—scores above 0.75 require manual review, scores between 0.5 and 0.75 depend on other factors, scores below 0.5 trigger automatic denial—so product teams know exactly when the ML prediction matters and when business rules override it.

Two ways to integrate ML:

Option 1: Treat the model output as a decision component, where the logic specification points to a model file in PMML or ONNX format instead of containing a decision table. You didn't write explicit rules for it; you're pointing to a machine learning definition your data scientists provided.

Option 2: Treat the model as an external service that returns a score, which then feeds into decision model logic as input data.

Either way, the boundary between probabilistic and deterministic reasoning is explicit.

Legal teams: focus compliance review on that boundary. You don't need to audit the ML training process every time someone tweaks approval thresholds, because the decision table documents exactly how scores map to outcomes.

Product teams: swap ML models—try a new risk scoring approach, A/B test different architectures—without touching the business logic layer.

Authority trails for each decision rule

Every decision table can link to a knowledge source that justifies its logic. If the credit tier rules depend on the enterprise credit policy version 3.2, that connection is documented in the model. If a loan-to-value rule implements Federal Housing Administration guidance, the model specifies which document section governs that rule. When regulators or internal auditors ask "where did this decision come from," you hand them the decision model with authority links intact.

The documentation pays off when rules change. If the FHA updates its LTV guidance, product teams know exactly which decision tables need revision because the authority links make dependencies explicit. Legal teams can compare the old and new authority documents, identify affected rules, and sign off on updates before they reach production. Otherwise you're searching through code to find what changed. That takes weeks, not hours.

Authority links also clarify who can approve rule changes. A subdecision governed by external regulation requires legal and compliance review before modification. A subdecision governed by internal operational policy might only need product owner approval. Decision models make those distinctions explicit rather than buried in change management documentation.

Capture decision logic before it becomes model training data

Legal teams: the audit happens before deployment rather than after production anomalies surface. You review the decision tables, confirm they match policy requirements, verify authority links point to current documents, and check edge case coverage. Gaps show up during design, not through customer complaints. Domain experts can review decision tables without reading code.

Product teams: that early validation prevents rework cycles. You don't build an LLM-based approval system, discover it produces inconsistent outputs for identical applications, then scramble to add rule layers on top. You start with decision models for the deterministic components, use ML where prediction actually helps, and avoid treating language models as general-purpose decision engines. LLMs "are not consistent" and "are not transparent," which matters when legal teams need to explain decisions to regulators or when product teams need to guarantee outcomes for contractual commitments.

Route ML scores through documented thresholds

The handoff point between ML predictions and business rules becomes a documented interface. The risk scoring model returns a number between 0 and 1, and the decision table defines what happens at every score range. If business requirements change—risk appetite shifts, new regulations impose stricter standards—you update the decision table without retraining the model. If the ML team improves prediction accuracy, they swap the model without touching business logic. The separation means each team owns a clean boundary with testable inputs and outputs.

Legal teams: when reviewing an approval decision, you trace the outcome back to a specific rule in a specific decision table, see which ML score fed into that rule, and verify the score itself came from a model that passed separate validation. You're not trying to explain why a transformer produced a particular token sequence. You're showing how documented rules processed structured inputs according to specified thresholds.

Build decision models before connecting them to ML

Decision models don't replace every AI component. Language models still handle unstructured input processing, customer communication, and tasks where variation is acceptable. But when the system makes a decision with legal or financial consequences—approve this loan, deny this claim, flag this transaction—route that decision through decision model logic where you can audit the rules, trace the authority, and guarantee consistency. The framework works because it solves a specific problem: making high-stakes decisions transparent and repeatable rather than hoping probabilistic systems converge on correct answers.

Build your decision models first. Start with the main decision. Break it down until each piece maps to one policy requirement or business rule. Write the decision tables. Link them to authority sources. Then figure out which subdecisions actually need ML predictions versus which ones just need deterministic logic. Most decisions need less ML than teams think, which means faster deployment and simpler compliance review.

Reference: Based on "A Beginner's Guide to Decision Model and Notation (DMN) for AI Agents"

Reference: